Chapter 3 A Short History of Climate Science

In this chapter, I will present a short history of the scientific discovery of the mechanisms that control Earth’s climate and cause it to change.

3.1 Joseph Fourier and the Greenhouse Effect

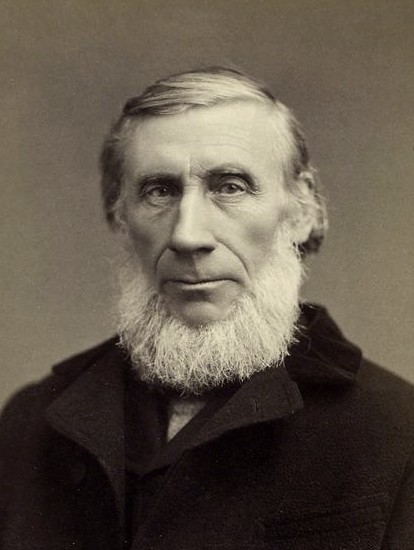

Figure 3.1: Joseph Fourier (engraving by Louis Leopold Boilly)

In the early 19th century, the French scientist Joseph Fourier was studying the flow of heat and in 1822 he published a very important book on the theory of heat. In the course of this work, Fourier applied his theories to the temperature of the Earth and calculated that if the Earth did not have an atmosphere, the balance of heat would make its temperature freezing cold (about 0°F). In fact, the average temperature of the Earth is around 63°F, so Fourier knew that the atmosphere was having a powerful effect on the flow of heat. (Fourier 1837) Fourier suggested that the atmosphere might be acting similarly to the way that in a greenhouse the panes of glass allow sunlight to bring heat into the greenhouse, but then prevent the heat from escaping. This was the discovery of the greenhouse effect, although Fourier did not use that exact phrase.

Fourier discovered that the atmosphere was trapping heat by absorbing infrared radiation and thus raising the surface temperature by more than 60°F. However, he did not know which constituents of the atmosphere were doing this. In 1856, an American scientist and women’s rights activist, Eunice Foote, published a report in The American Journal of Science and Arts in which she set jars containing different gases in the sunlight and compared their temperatures. Foote discovered that a jar containing carbon dioxide became about 20°F warmer than jars containing other gases, such as oxygen and hydrogen. (Foote 1856) Foote’s discovery was ignored for more than 150 years until 2010, when Ray Sorenson, a retired geologist, came across her paper and recognized its historical importance.

Figure 3.2: John Tyndall (photograph by Elliott & Fry)

Three years after Foote published her discovery, the Irish scientist John Tyndall reported the results of his own research, which showed that carbon dioxide and water vapor were the gases responsible for the greenhouse effect. (Tyndall 1872)

3.2 The Greenhouse Effect and Earth’s Changing Climate

While Fourier, Foote, and Tyndall were discovering the connections between the climate and the flow of radiant heat, other scientists, such as the Swiss geologist Louis Agassiz, were discovering that long ago, large parts of Europe and North America had been covered by gigantic glaciers.1 By the late 19th century it was clear that there had been not one but many periods in which glaciers had advanced to bury much of northern Europe and then retreated back to the high mountains. Geologists now call the ice age during which these cycles of glaciation occurred the Pleistocene epoch.

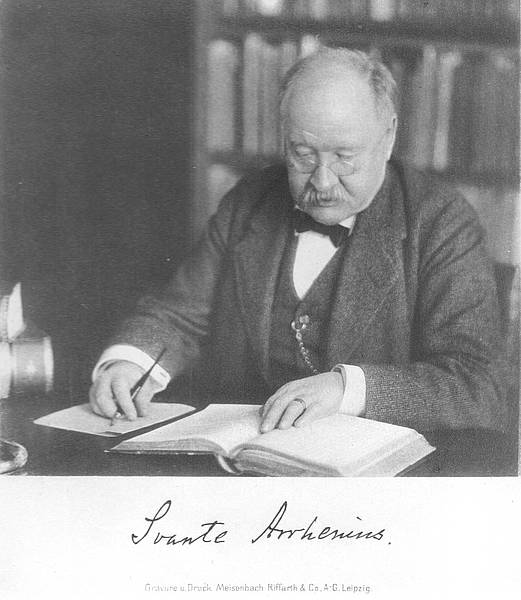

Figure 3.3: Svante Arrhenius (University Archives, University of Würzburg)

Scientists tried to figure out what could have caused the climate to have changed enough to create the glacial cycles ice-age glaciations. In 1898, the Swedish chemist Svante Arrhenius2 proposed that Fourier’s greenhouse effect might be the answer. If the amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere had changed over time, it could have produced temperature changes great enough to explain the ice age. (Arrhenius 1896)

Arrhenius went on to make another inference. If natural changes of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere had caused climatic change, then people burning coal would likely increase carbon dioxide levels and warm the planet up. (Arrhenius 1896; Arrhenius & Borns 1908) Arrhenius was living in Sweden at the turn of the 20th century and unlike people today, he thought global warming sounded like a great thing:

By the influence of the increasing percentage of [carbon dioxide] in the atmosphere, we may hope to enjoy ages with more equable and better climates, especially as regards the colder regions of the Earth, ages when the Earth will bring forth much more abundant crops than at present, for the benefit of rapidly propagating mankind. (Arrhenius & Borns 1908 p. 63)

As part of his work on understanding the ice age and predicting future warming, Arrhenius calculated an estimate of how much the Earth would warm up if the amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere doubled and how much it would cool if the amount of carbon dioxide decreased by half. His calculations were fairly simple by today’s standards, but are not too far from current estimates.

3.3 The Greenhouse Effect After Arrhenius

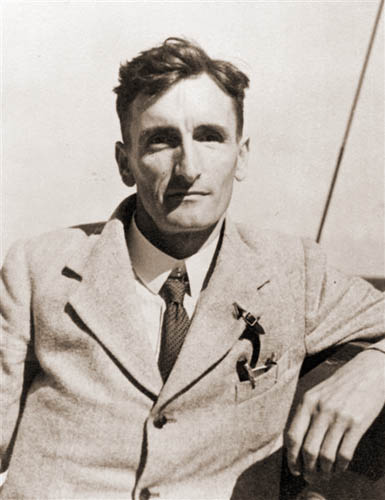

After Svante Arrhenius, scientific understanding of the greenhouse effect stalled out somewhat. The British engineer Guy Callendar pursued sophisticated amateur studies, as a hobby, from the 1930s through the early 1960s to measure the impact of rising CO2 levels on the world’s climate. Callendar was unable to prove that human activity was causing global warming, in part because the theory of the greenhouse effect was too imprecise to make detailed predictions.

Figure 3.4: Guy Callendar (University of East Anglia Archives)

The reason it was so hard to advance the theory of the greenhouse effect was that the calculations were far too difficult. Arrhenius had calculated his estimates of the greenhouse effect and global warming using pen and paper. The next steps of improving these estimates would require tens of thousands of calculations, using detailed measurements of the properties of water and carbon dioxide molecules.

Figure 3.5: Gilbert Plass (Emilio Segrè Visual Archives, American Institute of Physics)

These next steps only became practical in the 1950s when scientists could use electronic computers to automate repetitive calculations. In 1956, Gilbert Plass used one of the first computers to make detailed calculations of the greenhouse effect and he confirmed Arrhenius’s hypothesis that natural changes in carbon dioxide could explain the ice-age glaciations, writing that “there are many facts about world-wide variations in the climate that can be explained in a simple, straight-forward manner only by the CO2 theory.” (Plass 1956) These facts included details about the Pleistocene glaciations as well as the observed global warming during the first half of the 20th century.

Plass also confirmed Arrhenius’s speculations about global warming caused by people burning fossil fuels and predicted that

The extra CO2 released into the atmosphere by industrial processes and other human activities may have caused the temperature rise during the present century. … [T]he CO2 theory predicts that this warming trend will continue, at least for several centuries. — (Plass 1956)

References

Arrhenius, S. (1896). On the influence of carbonic acid in the air upon the temperature of the ground. Philosophical Magazine and Journal of Science, 41, 237–276.

Arrhenius, S., & Borns, H. (1908). Worlds in the making; the evolution of the universe, New York, London, Harper. Retrieved from http://archive.org/details/worldsinmakingev00arrhrich

Foote, E. (1856). Circumstances affecting the heat of the sun’s rays. American Journal of Science and Arts, 22, 382–383.

Fourier, J.-B. J. (1837). General remarks on the temperature of the terrestrial globe and the planetary spaces. American Journal of Science, 32(1), 1–20.

Plass, G. N. (1956). The carbon dioxide theory of climatic change. Tellus, 8(2), 140–154.

Tyndall, J. (1872). Contributions to molecular physics in the domain of radiant heat: A series of memoirs published in the ’Philosophical Transactions’ and ’Philosophical Magazine,’ with additions, Longmans, Green, and Company. Retrieved from http://books.google.com?id=mOAEAAAAYAAJ